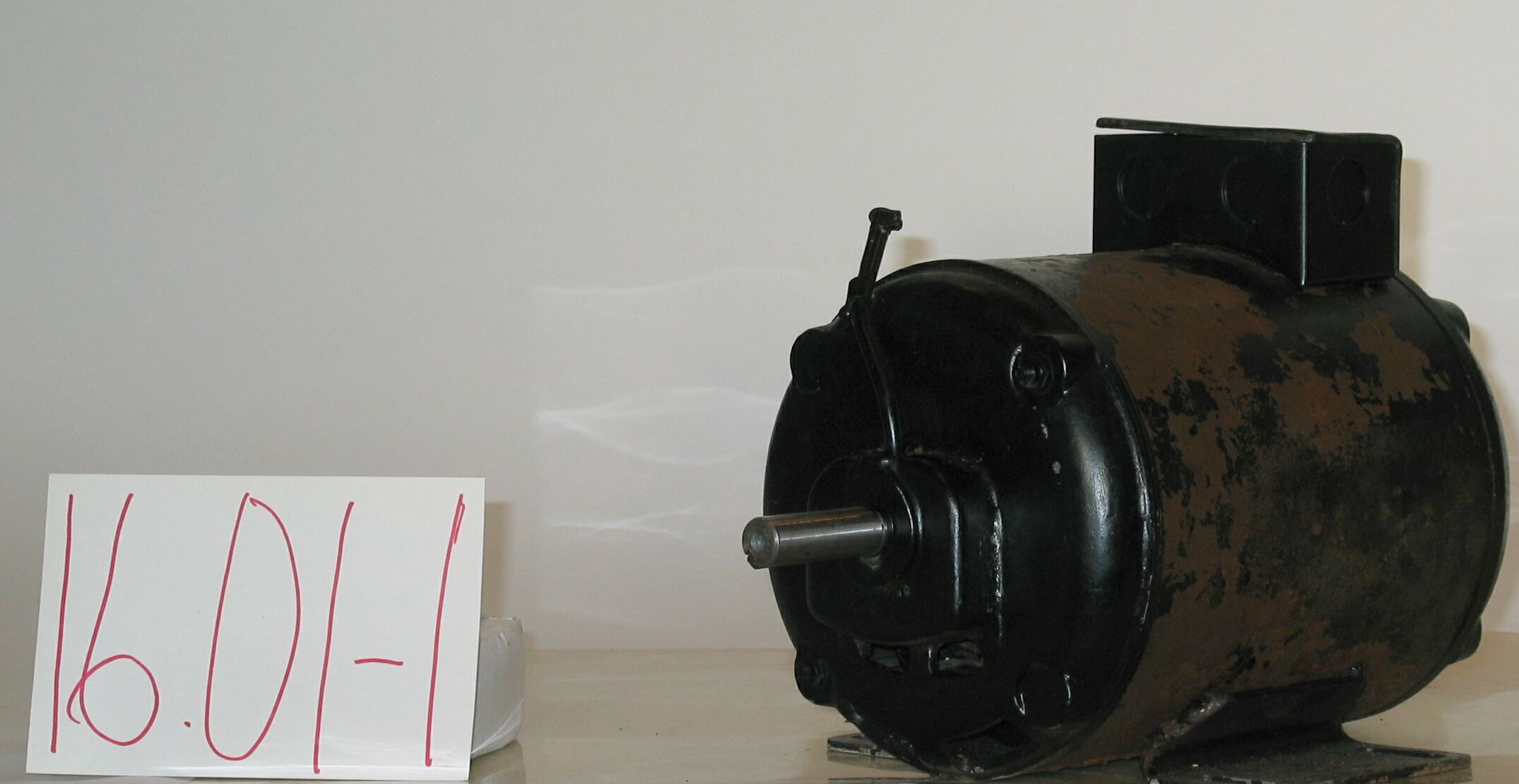

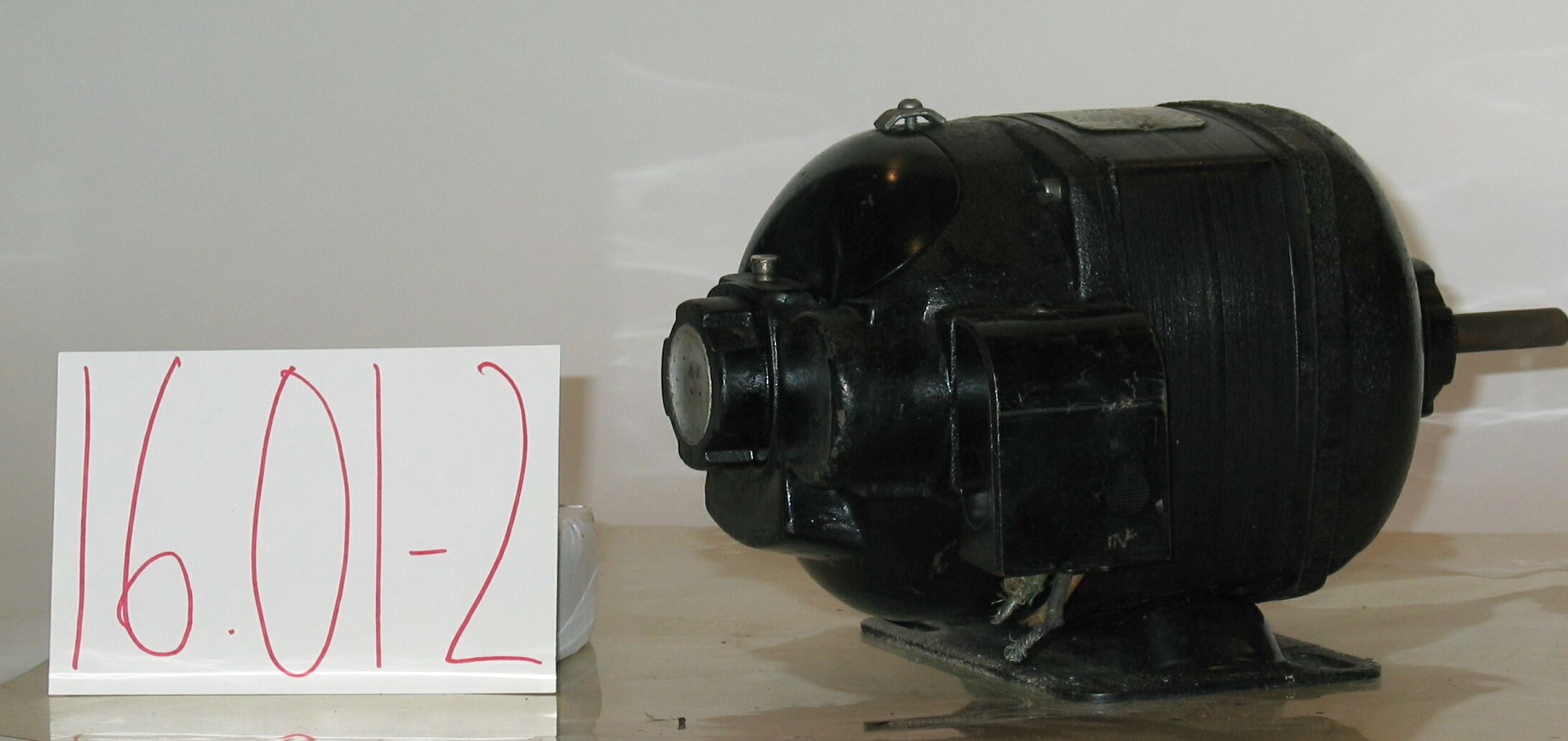

16.01-2: Leland 1960 Dual Voltage, Mechanically Reversible Motor

| HHCC Accession No. 2006.170 | HHCC Classification Code: 16.01-2 |

|---|

Description:

Classic mid 20th century, heavy duty, repulsion induction, brush lifting motor, dual voltage and mechanically reversible. Canadian made, it would characterize much of the Canadian experience through middle and latter years of the century, a period which saw massive growth in the demand for such high torque motors following W.W.II and frequency standardization. Yet, paradoxically, the period also witnessed the progressive demise of the technology, Leland [new and unused], Circa 1960. [See also ID# 308]

Group:

16.01 Electric Motors - Single Phase, Repulsion Induction and Repulsion Motors

Make:

Leland

Manufacturer:

Leland Electric Canada Limited, Quelph Ont.

Model:

Form AKWJH, Type R

Serial No.:

1674L2502 KF4636

Size:

12 x 7 x 7’h

Weight:

35 lbs.

Circa:

1960

Rating:

Exhibit, education, and research quality, illustrating the engineering and construction of a Canadian made, classic mid 20th century, heavy duty, repulsion induction motor,

Patent Date/Number:

Provenance:

From York County (York Region) Ontario, once a rich agricultural hinterlands, attracting early settlement in the last years of the 18th century. Located on the north slopes of the Oak Ridges Moraine, within 20 miles of Toronto, the County would also attract early ex-urban development, to be come a wealthy market place for the emerging household and consumer technologies of the early and mid 20th century.

This artifact was discovered in the 1950’s in the used stock of T. H. Oliver, Refrigeration and Electric Sales and Service, Aurora, Ontario, an early worker in the field of agricultural, industrial and consumer technology.

With shop tag in Howard Oliver’s hand writing, ‘checks OK, Jan 1975’

Type and Design:

Classic mid 20th century, heavy duty, repulsion induction, communtating motor, Brush lifting, Dual voltage, 110-220 volts Mechanically reversible, Bronze sleeve bearings with snap cap oilers, All steel ferro-magnetic body Steel slotted base plate, rigid mounted Built-in well for ‘Klixon’ motor overload protector with automatic reset, never installed in this motor frame [See ID#308] Built-in electrical junction box

Characterizing best Canadian practice through middle and later years of the 20th century

Construction:

Material:

Special Features:

Built-in well for the possible installation of ‘Klixon’ motor overload protector with automatic reset. Shop tag in Howard Oliver’s hand writing, ‘checks OK, Jan 1975’

Accessories:

Capacities:

Performance Characteristics:

Operation:

Control and Regulation:

Targeted Market Segment:

Consumer Acceptance:

Merchandising:

Market Price:

Technological Significance:

With a built-in ‘well’ making provision for ‘Klixon’ inherent motor overload protector technology, this artifact is a marker of the advances made by mid century in personal and property protection for the FHP motor owners. By then, the inherent, automatic overload projector with automatic reset had become a mainstream technology, for which provisions were being built into the motor body, whether the particular application required it or not. Inherent, automatic overload motor protection was a universal truth for FHP motor design by the middle of the 20th century. It was yet another indicator of the new world of advances made through automation - as it existed in the mid 20th century. Canadian made, this motor would characterize much of the Canadian experience through middle and later years of the century, in high torque, FHP motor development. A period which saw massive growth in the demand for such high starting torque motors, typically for use on refrigeration equipment, which flooded the market in those years, following W.W.II and frequency standardization. Repulsion induction motor technology was above all a marvel of its time, a technology born of both science and the consumer market place, a classic formula for the innovation and diffusion of popular technology,throughout the balance of the 20th century and on in to the 21st. Scientifically, the work of Faraday and many others laid much of the theoretical foundations for electromagnetic devices, the marvel of the early 20th century [much in the same way digital devices became the marvel of the early years of the 21st]. The wonders made possible by alternating current energised, rotating magnetic fields and the electric and magnetic circuitry that made them possible would soon be exploited by those interested in their application in applied electro-motive technology, including Steinnmetz and others. [See References especially #I, 2, and 5] For the Canadian household and commercial refrigeration industry, pioneered by Kelvinator and Frigidaire, it would be a ‘just-in-time’ technology, as well as an immensely enabling one - and what it enabled was considerable. Sir William Thompson, Lord Kelvin, had just set out the theoretical principles of the compression refrigeration, Carnot cycle [see Note #1]. But there existed no electro-motive devices with sufficient starting torque able to drive the compressor, making mechanical cooling practical for household and commercial uses ‘ even for those who were otherwise able to enjoy the benefits of electrification. The push was on to develop such a device, the repulsion induction, single-phase motor would quickly follow. But paradoxically, by the mid 20th century the market for high torque, repulsion induction motors, for household and commercial refrigeration applications had peaked. A technology of its times, it represented immense achievement by early 20th century engineers and manufactures. Yet, as is typically the case, with the innovation, dissemination and popularization of technology come the seeds of its own demise. The very means by which its high torque performance had been achieved, through the use of an elaborate wound rotor, commentator and electrical brushes, made it costly, clumsy and noisy, as well as unsuitable for many embedded applications, such as hermetic refrigeration and air conditioning systems. Replacing the commentator and complex rotor windings with a ‘solid state, squirrel cage’ rotor represented a giant engineering advancement. The development of capacitor start electric motor technology [see Classification 12.02] would now quickly replace repulsion induction technology for many applications, well before the end of the 20th century.

Industrial Significance:

Well recognized for their performance, reliability and maitainability, the repulsion induction engineering designs employed by Leland Electric, Quelph Ontario, along with Wagner Electric Leaside would in many ways serve to characterizing best Canadian practice through middle and later years of the century. Because of the specialized nature of the technology, engineering and production costs, and the limited market, few companies would be seen as surviving in the popular, repulsion induction market beyond mid century.

Socio-economic Significance:

Socio-cultural Significance:

Not-with-standing a major depression and two world wars the first half of the 20th century was a period of exceptional ferment in the development and popular dissemination of FHP electric motor technology. Associated with the development were a number of driving forces, mutually supporting and interacting: Scientifically, the theoretical ground work for development of an astonishing array of electrical and electro-magnet devices had been laid by the early years of the 20th century, through the efforts of Faraday and Steinnmetz, among many others, Technologically, the work of Thomas Edison, among others, laid the foundation stones on which urban and rural electrification would proceed, enabling an new era in human experience, favoured with consumer goods and services, previously unimagined,

Economically, a favourable climate for capital investment in manufacturing capacity, methods and materials emerged, part of North America’s second industrial revolution, Socially and culturally the consumer society was born, nurtured by a pent up demand for an easier, more comfortable, pleasurable lifestyle, and the sense that 20th century electrical and electro-motive technology might be able to help. The FHP electric motor, engineered for 110 volt, single-phase house current, revolutionized life in the Canadian home. It enabled an astonishing list of appliances and labour saving devices. The revolution would take place in an astonishingly short period of time - for much of urban Canada much less than a decade. The electro-mechanical mechanization of the Canadian home was accomplished for much of urban Canada by the late 1930’s. But the early 20th century wonders of household mechanization would be dependent , in turn, on household ‘electrification’ Between them electrification and electro-mechanical mechanization changed everything. Almost over night it altered what Canadians do in the course of their day, how they live and their expectations of what their world had in store for them - in labour saving devices, devices of convenience, health and safety. The fractional horsepower electric motor [FHP] became an ubiquitous part of the Canadian household by the mid 1930’s. Cyril Veinott reported, December 1938:

‘Practically every electrified home today makes use of one or more fractional horsepower motors. This kind of motor may be used in a washing machine, refrigerator, vacuum cleaner, clock, oil burner, hair drier, room heater, sewing machine, razor, health machine, fan, air conditioner, stoker, ironed, floor waxer, or food mixer. In industrial use, the number of useful tasks performed by fractional horsepower motors is legion. In the United States alone, the value of fractional horsepower motors sold amounts to approximately $50,000,000 annually.’ See reference #1

Similarly, more than half a decade earlier Daniel Braymer had commented on the proliferation of this mind and life changing technology for home electro-mechanization. He observed that what had made it all possible was the invention of single phase alternating current motor, in a number of subtypes, small quiet, self starting, reliable and affordable motors for the home, motors which were compatible with the rapid standardization of single phase, alternating current, electrical distribution systems then spreading across north America. See reference #2 Among the types of single phase alternating current motors which quickly populated the Canadian home were: repulsion induction [see Group 16.01] for heavy duty, high starting torque applications such as refrigeration appliances; capacitor start [see Group 16.02] for advanced high torque applications, requiring quiet operation; split Phase [see Group 16.04] for light duty low starting torque applications; and shaded pole [see Group 16.04] designs for small devices such electric fans. The FHP single phase induction motor, often unobtrusive, out of sight in a dark corner, has, none-the-less, been a principle foundation stone on which Canadian, popular consumer and household technology has evolved, throughout the 20th century and into the 21st - a driving force of profound, typically un-recognized, social, cultural and economic change [See reference 6]. Electro-motive technology [the FHP motor], along with electric and electronic communications technology [the telephone and broadcast radio] would invade the Canadian home starting in the 1920’s. Throughout the balance of the 20th century these technologies would trigger a vast, new, popular consumer culture, a ‘popular technological revolution’. Yet, simply because technology has so shaped the Canadian reality, it has also shaped much profound Canadian though about the technological experience, its meaning and significance for humanity. Included among the works of Canadian writers with an international reputation are: Arthur Kroker, George Grant, Ursala Franklin, Heather Menzies, among many others [See references 7, 8, 9, and 10]. From the vantagepoint of the 21st century noted Canadian writer Jane Jacobs asks, ‘Now we stand at another monumental crossroad, as agrarianism gives way to a technology-based future. How do we make this shift without losing the culture we hold dear’ [See reference 11]

Donor:

G. Leslie Oliver, The T. H. Oliver HVACR Collection

HHCC Storage Location:

Tracking:

Bibliographic References:

‘Fractional Horsepower Electric Motors’, Cyril Veinott, McGraw Hill New York, 1948 ‘Rewinding Small Motors’, Daniel Braymer and C.C. Roe, McGraw Hill, 1932 ‘Theory and Application of Capacitor-Start Induction Motors’, G. L. Oliver, Bachelor Thesis ,University of Toronto, Session 1951-52 ‘Modern Refrigeration and Air Conditioning’, Electric Motors, Chapter 7, Andrew Althouse and Carl Turnquist, Goodheart-Wilcox, 1960 ‘A course in Electrical Engineering, Volume II, Alternating Current’, Chester Dawes, McGraw Hill, 1934, Starting single Phase Induction Motors, P. 362. ‘The Fractional Horsepower Motor and its Impact on Canadian Society and Culture’, G. Leslie Oliver, Material History Review, Vol. 43, Journal National Museum of Science and Technology, 1996. ‘Technology and the Canadian Mind, Innis/ McLuhan/Grant’, Arthur Kroker, New World Perspectives, 1984. ‘Technology and Empire’, George Grant, Anansi, 1969, ‘The Real World of Technology’, Ursula Franklin, Anansi, 1993. ‘Fast Forward and Out of Control’, Heather Menzies, Macmillan, 1989 ‘Dark Ages Ahead’, Jane Jacobs, Random House, 2004

Notes:

Note 1:

Sir William Thompson, to become Lord Kelvin, was a pioneer of modern physics. Among many other things he laid the foundations for the field of thermodynamics on which HVACR technology depends for its theoretical foundations, including the theoretical Carnot cycle, the basis of refrigeration thermodynamics. Having been born in Ireland in 1824, dying in Scotland in 1907, he was raised to the peerage in 1892, as Baron Kelvin of Largs.

His fundamental contributions to modern science and technology are remembered and honoured by the company name ‘Kelvinator’, a company established a few short years after his death. Established in 1914 in the USA, Kelvinator would open a plant for the development and production of refrigeration equipment in London Ontario in 1928, likely Canada’s first manufacturer of HVACR equipment.