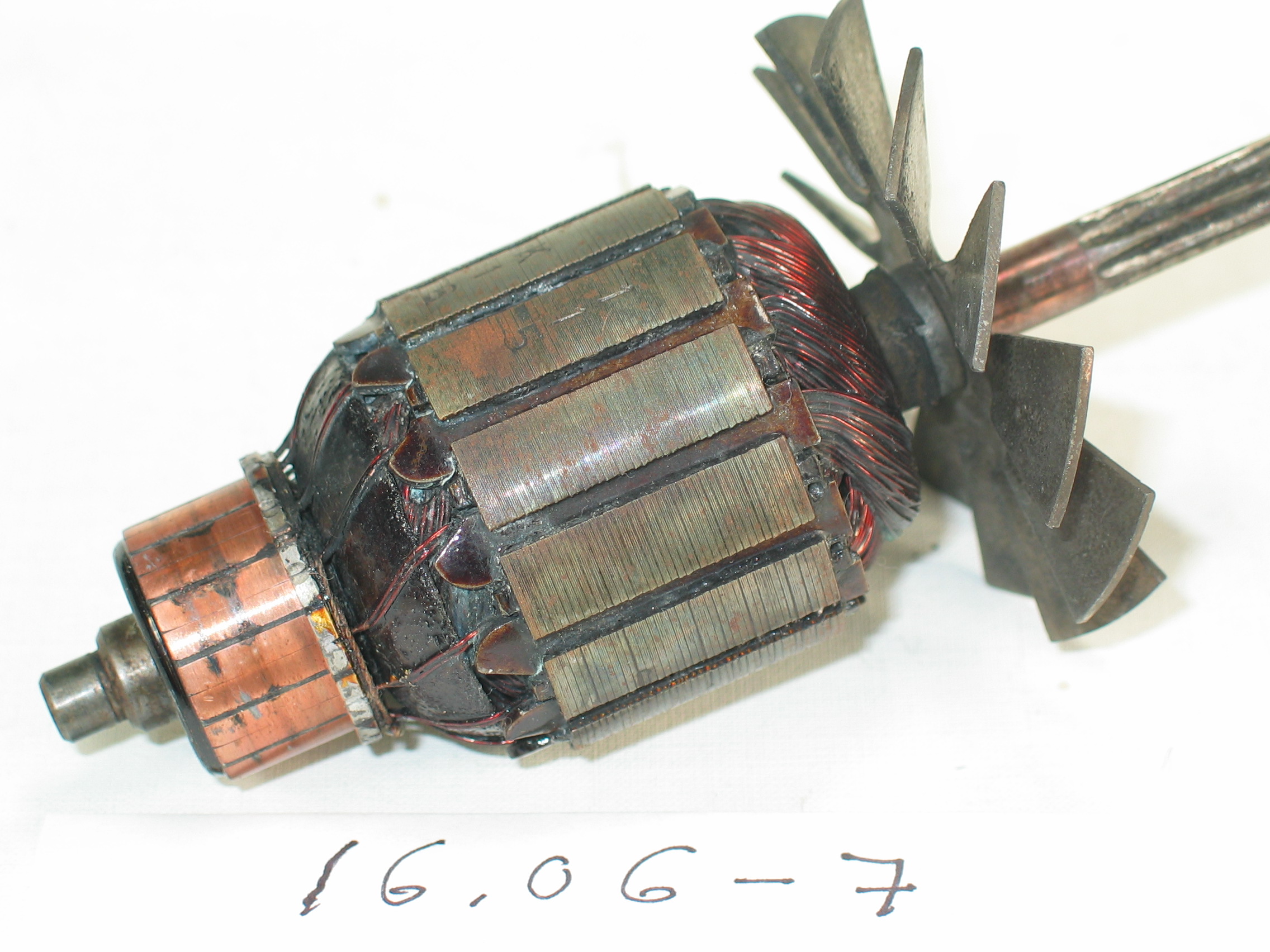

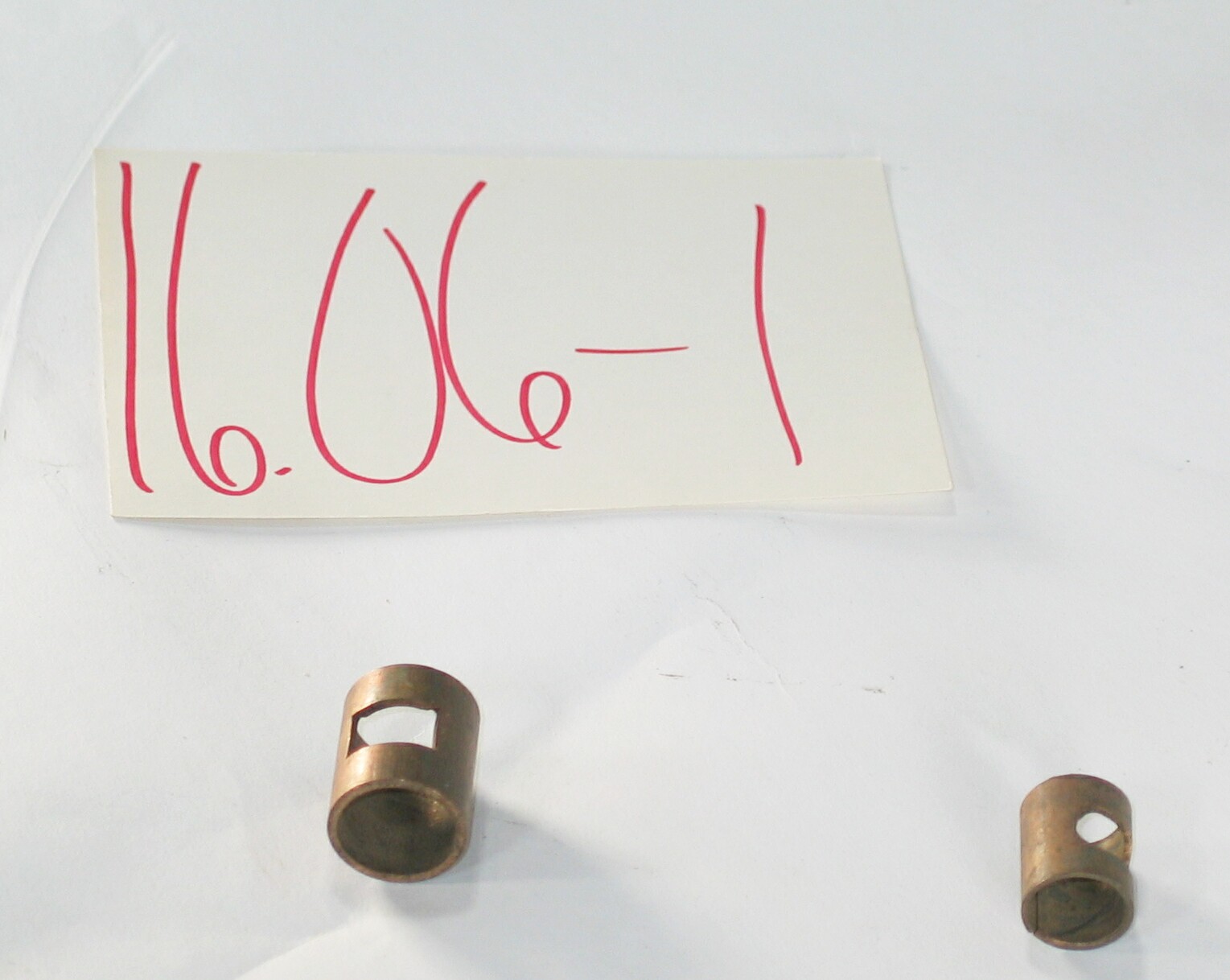

16.06-1: 1948 Electric Motor Sleeve Bearings

| HHCC Accession No. 2006.202 | HHCC Classification Code: 16.06-1 |

|---|

Description:

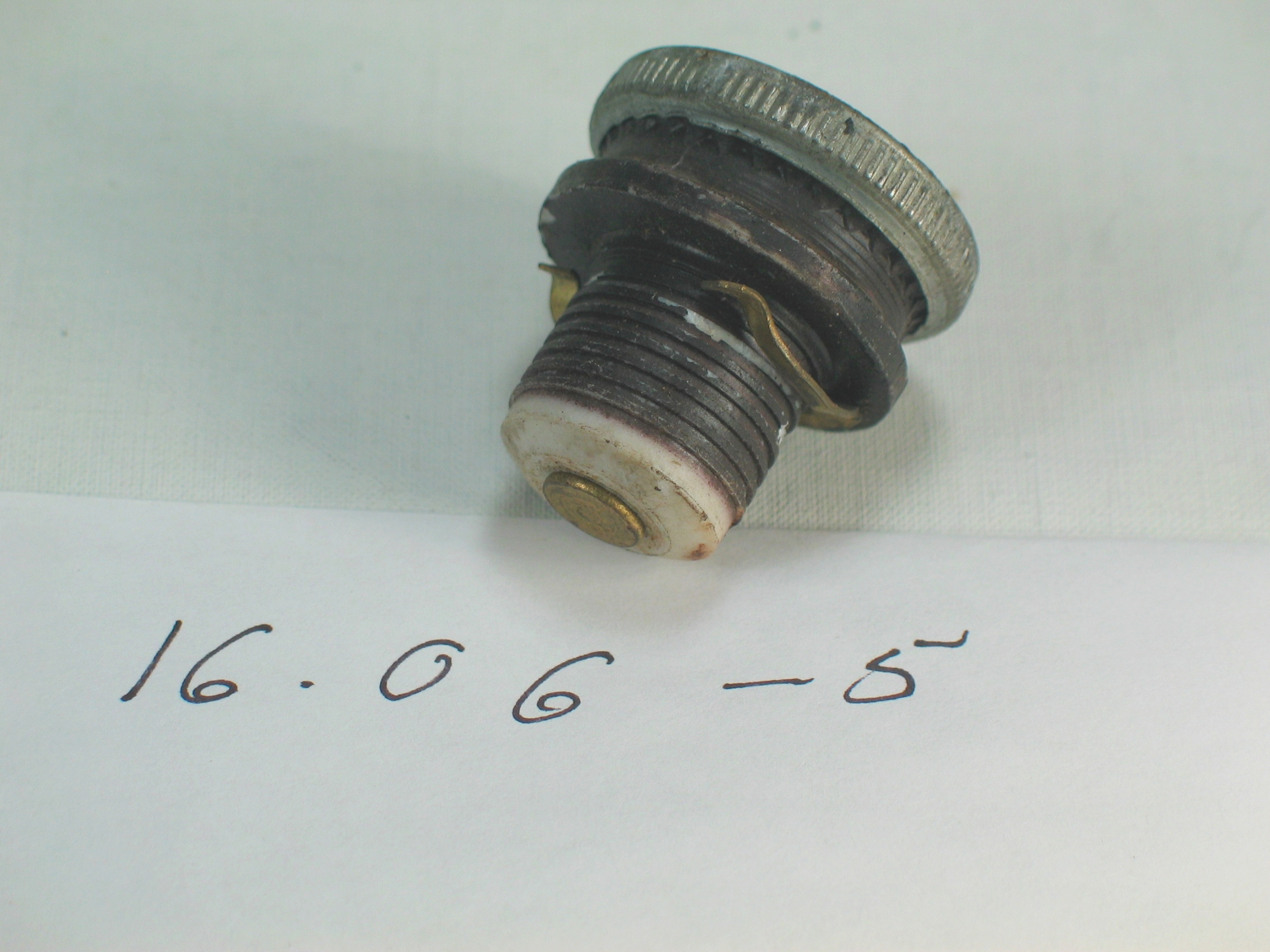

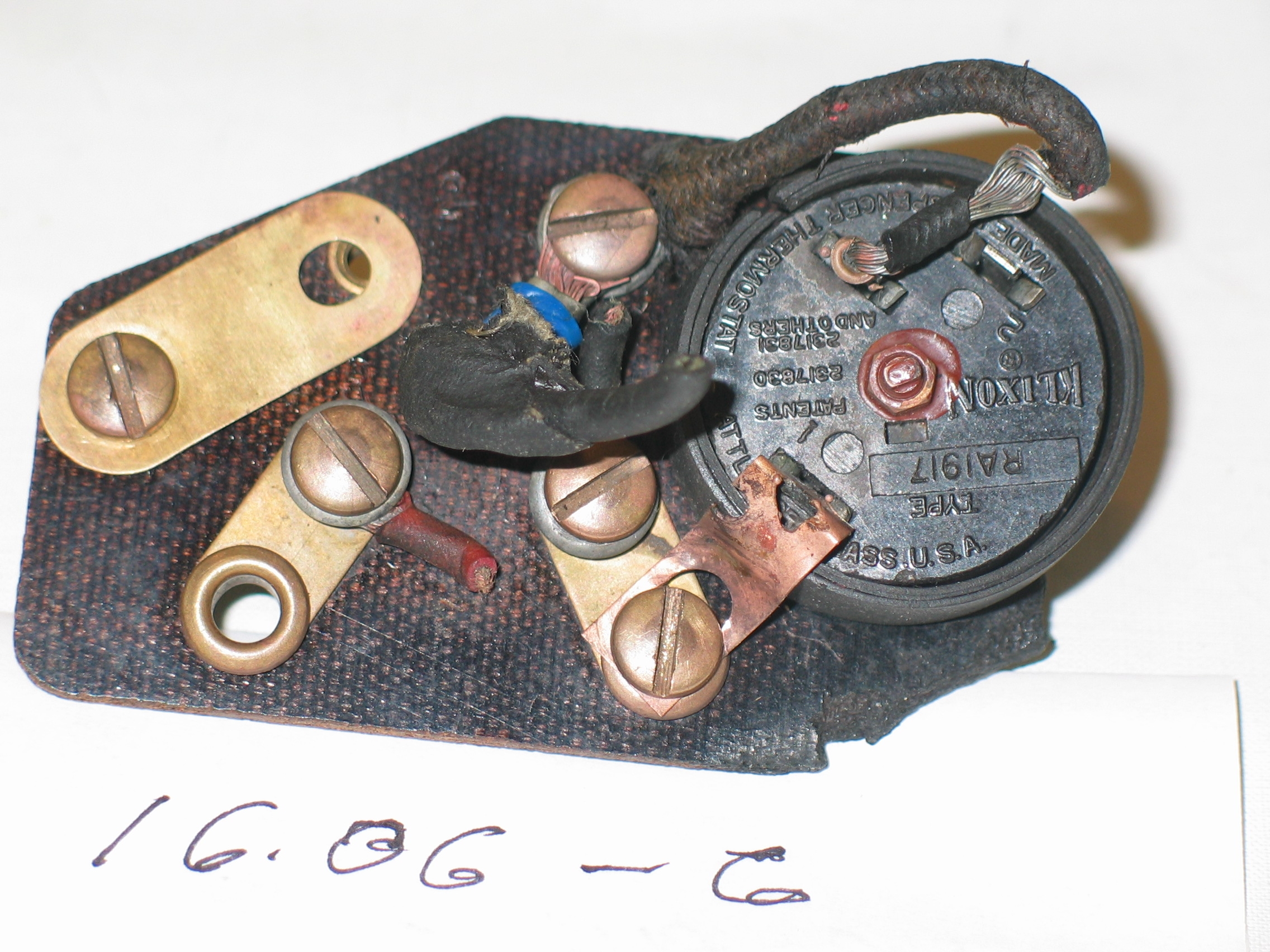

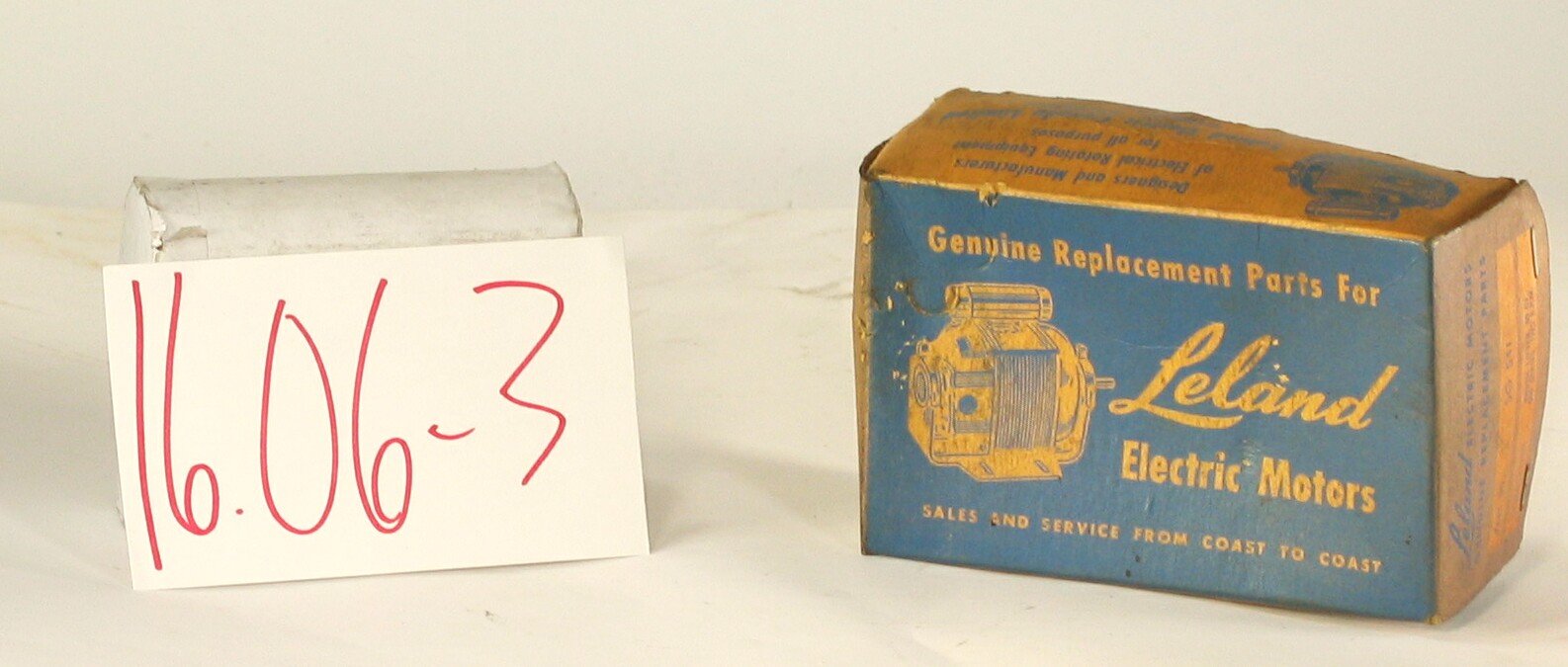

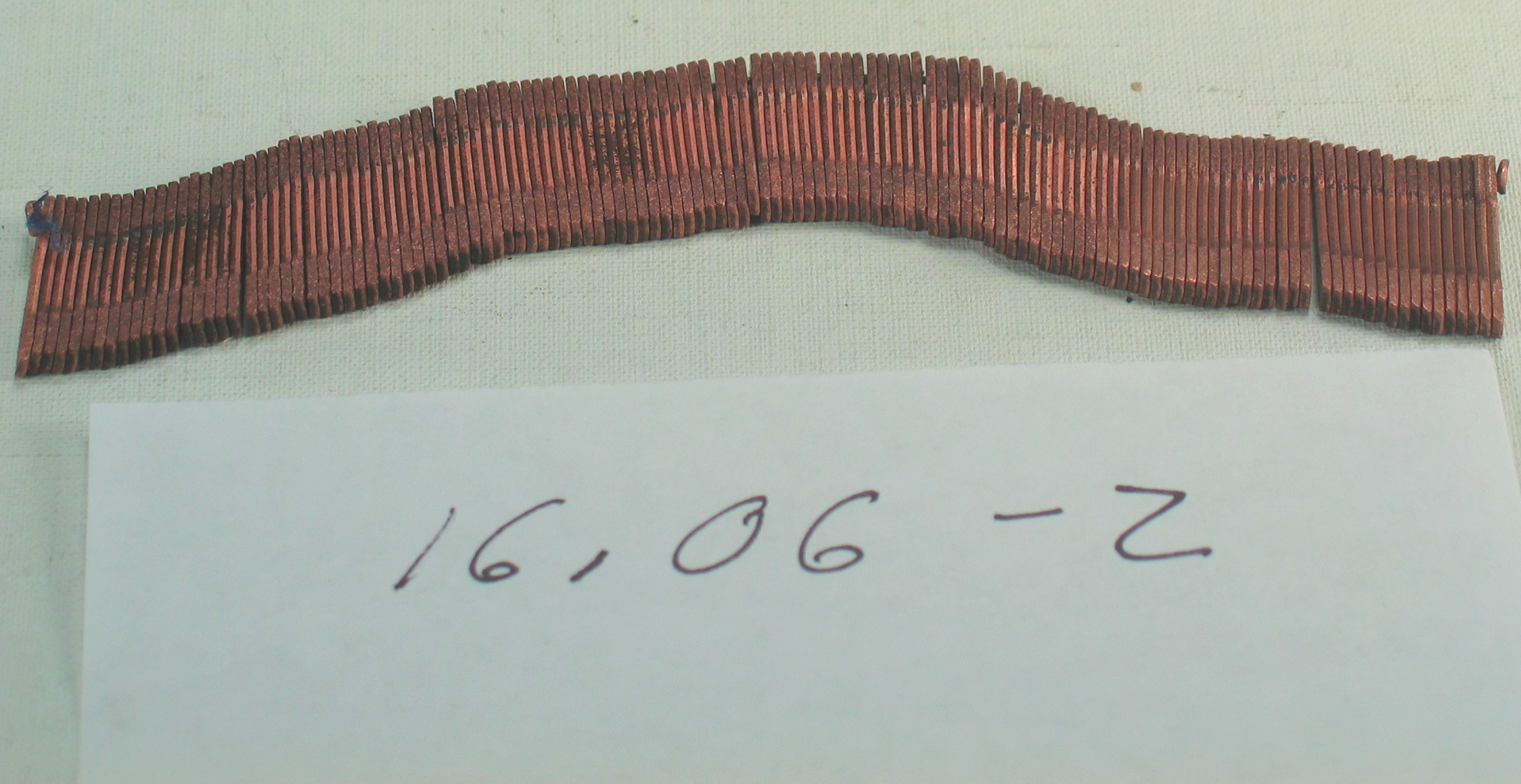

Early mid 20th century, bronze alloy, FHP electric motor sleeve bearings, split bearing design, with spiral oil grooves, adapted for automatic wick oiling. A ‘state-of-the-art’, self oiling bearing developed for electric motors for use in Canadian homes, where long life and reliable performance would be expected, without the constant attention of an ‘operating engineer’ with oil can in hand [set of two], manufacturer unknown, Circa 1948.

Group:

16.06 Electric Motors - Components and Parts

Make:

Unknown

Manufacturer:

Model:

Serial No.:

Size:

1 @ 15/16 x 1 1/8 inch 1 @ 23/32 x 15/16 inch

Weight:

2 0zs.

Circa:

1948

Rating:

Exhibit, education, and research quality, illustrating the state of the art in FHP bearing design as the mid 20th century approached ‘ a period well before the engineering and metallurgy requirements for long life motor bearings were understood.

Patent Date/Number:

Provenance:

From York County (York Region) Ontario, once rich agricultural hinterlands, attracting early settlement in the last years of the 18th century. Located on the north slopes of the Oak Ridges Moraine, within 20 miles of Toronto, the County would also attract early ex-urban development, to be come a wealthy market place for the emerging household and consumer technologies of the early and mid 20th century.

This artifact was discovered in the 1950’s in the used stock of T. H. Oliver, Refrigeration and Electric Sales and Service, Aurora, Ontario, an early worker in the field of agricultural, industrial and consumer technology.

Type and Design:

Bronze alloy, sleeve bearing Split bearing design Spiral oil grooves, Engineered for automatic wick oiling

Construction:

Material:

Special Features:

Accessories:

Capacities:

Performance Characteristics:

Operation:

Control and Regulation:

Targeted Market Segment:

Consumer Acceptance:

Merchandising:

Market Price:

Technological Significance:

A rare early glimpse of FHP electric motor bearing engineering as it existed in the middle years of the 20th century. It was a period characterized by much research and trial and error engineering aimed at producing a bearing metals which would perform reliably at modest speeds [up to 2000 rpm] with transverse, belt loading, in an unattended home environment. For here there was no operating engineer routinely inspecting the machinery of the home, with oil can in hand. Writing in 1936, reflecting on the state-of-the-art, Christopher Bierbaum noted:

‘Bearing metals are alloys composed of two or more metals in proportions in which they do not enter into a solid solution. They consist of relatively hard and soft microscopic particles or crystals intimately mixed.

The function of the hard particles or bearing crystals is to support the load and resist the wear at times when actual metallic contact exists between the bearing surfaces. The softer particles, in a measure, owing to their plasticity, allow the harder particles to adjust themselves to the surface requirements of the journal.

The softer particles also wear down lower than the harder particles and thus form slight depressions on the apparently smooth bearing surface. These depressions retain some of the lubricant and thereby effect a residuary lubrication, sufficient to prevent scoring or cutting during metallic contact.

The property of a metal to retain lubrication upon a ‘run-in’ bearing surface characterizes it as a bearing metal, and its capacity for doing so largely determines its value as such. A bearing metal, therefore, may be defined as an alloy that is capable of retaining a lubricant upon a bearing surface.’

The author goes on to elaborate the engineering practices of the day talking to the composition and properties of bronze bearing alloys variously in use, including percentages of: copper, aluminium, tin, lead, nickel and phosphorous being experimented with and the bearing performance characteristics that could be expected accordingly. [See Reference 5]

Industrial Significance:

Moving electro motive equipment into the Canadian home brought with many engineering challenges, not the least of which were matters of maintenance, as well as protection against personal and propriety damage for the home owner, as na’ve equipment owner/operator. So long as motive equipment remained in an industrial setting the likelihood was that there would be experienced operating engineers who were trained to keep the equipment properly oiled and adjusted. This was no longer a reasonable working assumption for motors and appliances in the home. Systems and materials for automatic oiling were devised with modest success, at first. [see ID# 333, oil wicking] The bearing materials and configurations of the mid 20th century would produce a sleeve bearing, with a possible 5 year life expectancy, if the oil wells were kept full by the householder, typically requiring attention quarterly. In the 1930-40’s, high tech bearing alloys and sealed bearing designs for extended life, without the need for regular oiling, where still well in the future. Oiling of motors and related appliances in the home would become a part of the appliance serviceman’s job, as would bearing replacement, often due to premature bearing failure where regular oiling was not part of a systematic maintenance. The well equipped service shop would be one in which a wide range of replacement bearings were on hand and as well as the specialized tools for installing and fitting them [See 16.07 series artifacts]

Socio-economic Significance:

Socio-cultural Significance:

Moving the ‘engines of industry’ in the home and places of business started with the ear-splitting noise of the internal combustion engine. By the 1920’s the principle cultural images in North America were said to be those of the engine and the mechanization that ensued. The engine had, in fact, become, in the dominant popular view, the ‘engine of progress’. It was seen everywhere, on the farm, in industry, in the shop, on the road and then, in a manner once thought not possible, in the home. A standard Canadian engineering text reported in 1946 that: ‘Ceaseless change is the keynote of the machine age and society’.Machine civilization ‘.differs from others in that it is dynamic, containing within itself the seeds of constant reconstruction’’ The authors go on to note: ‘But machine civilization based on technology, science, invention, and expanding markets must of necessity change ‘ and rapidly. The order of steam is hardly established before electricity invades it; electricity hardly gains a fair start before the internal combustion engine overtakes it.’ See reference 11 Not-with-standing a major depression and two world wars the first half of the 20th century was a period of exceptional ferment in the development and popular dissemination of FHP electric motor technology. Associated with the development were a number of driving forces, mutually supporting and interacting: Scientifically, the theoretical ground work for development of an astonishing array of electrical and electro-magnet devices had been laid by the early years of the 20th century, through the efforts of Faraday and Steinnmetz, among many others, Technologically, the work of Thomas Edison, among others, laid the foundation stones on which urban and rural electrification would proceed, enabling an new era in human experience, favoured with consumer goods and services, previously unimagined,

Economically, a favourable climate for capital investment in manufacturing capacity, methods and materials emerged, part of North America’s second industrial revolution, Socially and culturally the consumer society was born, nurtured by a pent up demand for an easier, more comfortable, pleasurable lifestyle, and the sense that 20th century electrical and electro-motive technology might be able to help. The FHP electric motor, engineered for 110 volt, single-phase house current, revolutionized life in the Canadian home. It enabled an astonishing list of appliances and labour saving devices. The revolution would take place in an astonishingly short period of time - for much of urban Canada much less than a decade. The electro-mechanical mechanization of the Canadian home was accomplished for much of urban Canada by the late 1930’s. But the early 20th century wonders of household mechanization would be dependent, in turn, on household ‘electrification’ Between them electrification and electro-mechanical mechanization changed everything. Almost over night it altered what Canadians do in the course of their day, how they live and their expectations of what their world had in store for them - in labour saving devices, devices of convenience, health and safety. The fractional horsepower electric motor [FHP] became an ubiquitous part of the Canadian household by the mid 1930’s. Cyril Veinott reported, December 1938:

‘Practically every electrified home today makes use of one or more fractional horsepower motors. This kind of motor may be used in a washing machine, refrigerator, vacuum cleaner, clock, oil burner, hair drier, room heater, sewing machine, razor, health machine, fan, air conditioner, stoker, ironed, floor waxer, or food mixer. In industrial use, the number of useful tasks performed by fractional horsepower motors is legion. In the United States alone, the value of fractional horsepower motors sold amounts to approximately $50,000,000 annually.’ See reference #1

Similarly, more than half a decade earlier Daniel Braymer had commented on the proliferation of this mind and life changing technology for home electro-mechanization. He observed that what had made it all possible was the invention of single phase alternating current motor, in a number of subtypes, small quiet, self starting, reliable and affordable motors for the home, motors which were compatible with the rapid standardization of single phase, alternating current, electrical distribution systems then spreading across north America. See reference #2 Among the types of single phase alternating current motors which quickly populated the Canadian home were: repulsion induction [see Group 16.01] for heavy duty, high starting torque applications such as refrigeration appliances; capacitor start [see Group 16.02] for advanced high torque applications, requiring quiet operation; split Phase [see Group 16.04] for light duty low starting torque applications; and shaded pole [see Group 16.04] designs for small devices such electric fans.

Donor:

G. Leslie Oliver, The T. H. Oliver HVACR Collection

HHCC Storage Location:

Tracking:

Bibliographic References:

‘Fractional Horsepower Electric Motors’, Cyril Veinott, McGraw Hill New York, 1948 ‘Rewinding Small Motors’, Daniel Braymer and C.C. Roe, McGraw Hill, 1932 ‘A course in Electrical Engineering, Volume II, Alternating Current’, Chester Dawes, McGraw Hill, 1934, Starting single Phase Induction Motors, P. 362. ‘The Fractional Horsepower Motor and its Impact on Canadian Society and Culture’, G. Leslie Oliver, Material History Review, Vol. 43, Journal National Museum of Science and Technology, 1996. ‘Handbook of Engineering Fundamentals’, Ovid Eshbach, First edition 1936, Eleventh printing April 1947, Section 11-84, Bearing Metals.